|

| Definition, Urban Dictionary |

What does re-accommodate mean to you? To adjust? To adapt? Unfortunately for United Airlines it is now a euphemism for violently assaulting your passengers – which has left a lasting blow to their reputation.

Reputation

is everything. In markets often inundated by choice it can give organisations

an advantage over their competitor. And while reputation is difficult to build

and sustain, it can be easily damaged. So, when a crisis does tarnish your

reputation, how do you restore it?

Image Repair Theory

Benoit created Image Repair Theory as guidance for different strategies that can be utilised in a crisis. These can be categorised as (i) denial, (ii) evasion of responsibility, (iii) reducing offensiveness, (iv) corrective action and (v) mortification. Dependent on the crisis and the stage it is at, multiple strategies may be required. Nonetheless, when applied correctly these strategies can help practitioners to mitigate reputation damage. However, not all organisations know how to translate theory into practice.United Airlines

United Airline’s crisis began when a video emerged of a passenger being forcefully removed from one of its flights. The

video, originally posted by a fellow passenger on Facebook, went viral and was

subsequently picked up by major media outlets. In the aftermath, United’s CEO

issued an initial statement which endeavoured to downplay the event and

apologised for having to “re-accommodate” four passengers. This statement

triggered outrage and ridicule, with calls to boycott the airline circulating

on social media. The crisis further intensified when an internal memo was

leaked, showing United’s CEO reinforcing his support for employees and criticising

the behaviour of the passenger. United’s market value plummeted. This prompted

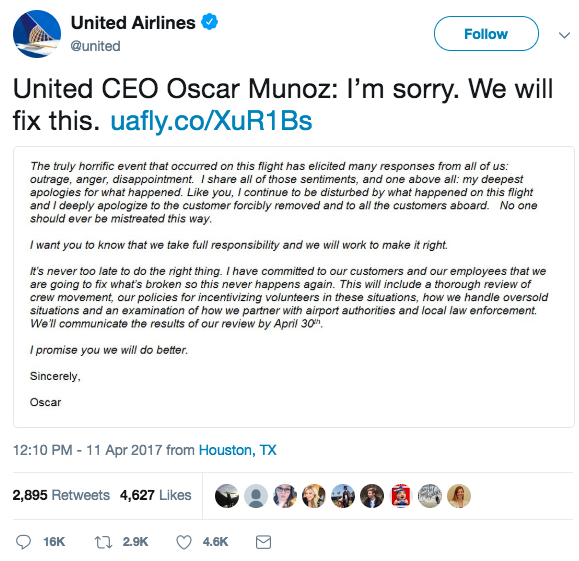

a second apology, one in which United took responsibility for the “truly

horrific event that occurred”, with a promise to “do better”.

|

| United's first statement, Twitter |

| |

|

Applying Benoit’s Image Repair Theory to United we can see their attempt to repair their

reputation evolved through four of the strategies. Firstly, reduce offensiveness was applied when

the CEO tried to downplay the event as simply “re-accommodating customers”.

This was quickly followed by evading

responsibility through placing the blame on the behaviour of the passenger.

Finally, as the outrage towards United persisted the CEO drastically changed

his message, opting for mortification

by way of an apology and corrective

action through amending the overbooking policy.

We

can conclude that United’s initial strategy to reduce offensiveness and evade

responsibility didn’t work, resulting in the need to take further steps to

repair their reputation. However, this case is more than strategic pivots.

Further exacerbating the crisis is United’s messaging through their CEO. Van der Meer states that the public’s interpretation of a crisis is guided by

information provided by influential sources and those sources can have more

impact during a crisis than under normal circumstances. With United’s CEO (the

source) not issuing an empathetic initial response, despite the existing

damning video evidence, he constructed many of the frames himself. The public

as a result were guided to act even more negatively and further damage United’s

reputation. How long it will take them to restore it? Only time will tell.

_______________________________________________________________

About the author:

Natalie Henshall is a Communication Science Masters student at the University of Amsterdam, specialising in persuasive communication. She has previous experience in communications, marketing and PR gained from working in the UK public sector. Her interests include social media engagement and health communications.

_______________________________________________________________

Benoit,

W. L. (1997). Image repair discourse and crisis

communication. Public Relations Review, 23(2),

177-186.

Benoit, W. L. (2018). Crisis and image repair at united

airlines: Fly the unfriendly skies. Journal

of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research, 1(1), 11-26.

Van der

Meer, T. (2018). Public frame building: The role of source usage in times of

crisis. Communication Research,

45(6), 956-981.

___________________________________________________________About the author:

Natalie Henshall is a Communication Science Masters student at the University of Amsterdam, specialising in persuasive communication. She has previous experience in communications, marketing and PR gained from working in the UK public sector. Her interests include social media engagement and health communications.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten